NEW YORK—Something very strange is happening in Room 306 of the Lorraine Motel. Playwright Katori Hall takes us into the room to reveal what it might have been like to be in the Memphis room in April 1968 on the night before the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. In the room, we watch a civil rights icon flirt, curse, get rattled by lightening, smoke Pall Malls, sip booze, acknowledge his stinky feet and even have a pillow fight with a young woman.

NEW YORK—Something very strange is happening in Room 306 of the Lorraine Motel. Playwright Katori Hall takes us into the room to reveal what it might have been like to be in the Memphis room in April 1968 on the night before the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. In the room, we watch a civil rights icon flirt, curse, get rattled by lightening, smoke Pall Malls, sip booze, acknowledge his stinky feet and even have a pillow fight with a young woman.

It is as audacious as it is inventive -- a simple premise that allows Hall to create a fictional universe of her own with a historical giant. It is also somewhat sacrilegious, showing the fleshy, banal side of a civil rights saint, which is partly the playwright's goal, too.

Her thrilling, wild, provocative flight of magical realism opened Thursday at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre with just two characters, Samuel L. Jackson as King and Angela Bassett as a mysterious motel maid who visits his room with coffee.

"I'm not perfect," King tells the woman, Camae.

"That you ain't!" she replies.

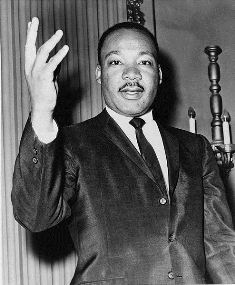

Jackson, who was an usher at King's funeral, shows King to be proud, fussy, funny, sad, vain, mugging, lecherous, kind and frightened. He modulates his voice when throwing out potential lines for a speech but keeps that hallowed voice far from his normal conversation, further separating the public King and the private man. In certain light, with his thin mustache and tightly cropped hair, Jackson eerily resembles his real-life model. At other times, he is just the "Snakes on a Plane" dude in a white shirt.

Bassett, on the other hand, is not mimicking any real person and so has the freedom to create -- and she does indeed. Camae comes into the room announcing that it's her first day on the job. At first, she seems overawed at being with King and her theatricality is a little over-the-top but that doesn't last.

Soon, she's swearing, teasing and sharing her flask of booze, cigarettes and her thoughts on the futility of peaceful protests with a man who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and inspired a 30-foot stone on the National Mall.

"Walkin' will only get you so far, Preacher King," she says impishly.

"We're not just walking; we're marching," he says.

Bassett's character arc is a wonder to behold and she delivers one of her best performances since she played Tina Turner in "What's Love Got to Do with It." Her Camae starts off obsequious, grows sassy, then bureaucratic, and finally ends by being all-knowing.

The play made its world debut in London and was the winner of the best new play Olivier award in London last year. Since then, a new cast and a new director, Kenny Leon, have jumped aboard.

Allusions to death are everywhere, and take on added weight since the audience knows this is King's last night on Earth. "Over my dead body," King says at one point to his visitor. Thunder and lightning as a storm rages outside jolt King, a touch that sounds potentially hokey but works here both as a signal of the weeping heavens and the recoil of an assassin's gun.

David Gallo's set is a meticulous reproduction of King's room at the Lorraine Motel. As the play unfolds, the room takes on a tomblike claustrophobia, before breaking apart wondrously in the final scene, a bit like what Hall's script has done to history. Despite the confining space, Leon has both King and Camae moving across the stage as they conduct their strange ballet.

Hall keeps her audience guessing about what will happen between King and Camae, and how far she is willing to pull the man down from his pedestal. Will we watch the beginning of an affair? Will King change his views on peaceful protest? And who exactly is Camae? Hall's answers come in time and then she's off on another magical tour through history.

This is playwrighting without a net, a defiant poke in the eye of all historical conventions and political correctness. Watching King in a pillow fight or plead for life might not be what people came in expecting to see -- or want to see -- but it serves the purpose of further breaking the polite spell that has kept King coolly removed from everyday life. The King that is left after Hall's humanization project is somehow more real and urgent and whole.

The inevitable standing ovations after the play are for King as much as for the actors and Hall.

- Home

- News

- Opinion

- Entertainment

- Classified

- About Us

MLK Breakfast

MLK Breakfast- Community

- Foundation

- Obituaries

- Donate

11-08-2024 6:51 pm • PDX and SEA Weather