Stacey Triplett was 28 years old when her doctor found fibroid tumors in her uterus. AnnMarie Rainford was 32.

Both women faced the possibility of having a hysterectomy in the prime of their lives.

"When I was diagnosed, they told me my tumor was the size of an orange," says Rainford. "I was asymptomatic and unsure about my plans for childbearing, so I decided to wait and see."

Triplett also waited. Every six months, for 12 years, Triplett visited her gynecologist for regular ultrasounds. The tumors continued to grow, but Triplett wanted to save her uterus.

"I thought I was being very conservative," Triplett says. "Despite having received advice to have my uterus surgically removed or carved up, I searched for better treatment options and waited for the day the fibroids would eventually stop growing."

Both Portland women became quasi experts in the realm of fibroids. What they discovered is that, as young African American women, they stood a much greater chance of having fibroids – benign tumors that cause problems like heavy bleeding and anemia and can greatly impact a woman's fertility – than their White counterparts.

According to a 1999 report by the National Women's Health Information Clinic, Black women have a 50 percent chance of developing fibroids, compared to White women's 33 percent chance.

What's more, of the 600,000 hysterectomies performed each year in this country, about half are related to fibroid tumors.

"I watched and waited for about four years," Rainford says. "But my fibroid was getting larger. I was diagnosed in 2001 and by 2005 it had grown from the size of an orange to the size of a grapefruit."

Doctors described Rainford's uterus as being the size of a five-month pregnancy. Eventually, Rainford's doctor referred her to a specialist who performed myomectomies. The procedure, which removes the fibroid without removing the uterus, still carries risks. Triplett knew of many friends who had received myomectomies for their fibroid tumors, only to require hysterectomies after suffering from complications to their uterine walls. In Triplett's mind, a myomectomy carried no guarantee that her uterus would be saved.

As it turned out, Rainford's fibroids were considered too large for the procedure. Hormone replacement therapy might shrink the tumors, but Rainford's insurance provider, Regence Blue Cross Blue Shield, refused to pay for the expensive treatments.

"Each shot was $600 plus I would have needed estrogen to decrease the effects," Rainford says. "When the insurance called and said they wouldn't pay for the hormone replacement ... the next step was embolization."

Uterine Fibroid Embolization is a non-surgical procedure that has gained national attention in recent years for helping women get rid of fibroid tumors without invasive surgery.

"Because of the risks associated with (surgery), my preference was embolization," Rainford says.

When she called Regence to inquire about UFE, Rainford was told that her insurance covered the procedure as long as it was "medically necessary."

In February of 2006, Rainford started researching Portland area doctors who performed the procedure. Her search led her to Dr. John Kaufman at Oregon Health Sciences University.

By 2006, Triplett knew her days of "watching and waiting" were over.

The tumors inside Triplett's body had distended her uterus to the size of a 20-week pregnancy.

"They were about the size of five good-sized sweet potatoes," Triplett says.

Doctors had advised her to remove the fibroids in the past and, by 2006, Triplett was ready to heed their warnings.

After talking to other women who had had good experiences with Dr. Kaufman, Triplett consulted the OHSU physician. She was a good candidate for the non-surgical embolization procedure, Kaufman told her. And after checking with her insurance provider – Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon – Triplett, like Rainford, was told that the procedure was covered, as long as "it was medically necessary."

When she asked the representative from Regence who decided if the procedure was "medically necessary," says Triplett, he told her the doctor would make that decision.

In June of 2006 both Triplett and Rainford had embolizations.

Six months later, both women – at this point still strangers – received similar letters from Regence BlueCross BlueShield.

The insurance company had refused to pay for the embolizations. Both Triplett and Rainford owed close to $20,000.

The reason?

"They said it wasn't medically necessary," Triplett says. "And then they said I hadn't taken conservative measures."

Rainford was told the same exact thing.

In the insurance provider's list of reasons for not paying for UFE, Regence BlueCross BlueShield cites "failure of conservative treatment (i.e. hormone replacement therapy)."

"But they wouldn't pay for the hormone replacement therapy," Rainford says. "It's so frustrating."

In Triplett's case, a host of doctors have sent letters to Regence on the Portland woman's behalf, stating that Triplett treated her fibroids conservatively for 12 years.

"Had Stacey not been adamant about conservative management, most physicians would have recommended hysterectomy or possibly myomectomy with a risk of hysterectomy," says Carol Suzuki, a physician Triplett went to while living in Boston, Mass. "Due to her young age and the conglomeration of her fibroids, I believe fibroid embolization was a happy medium ... which (saved) her from a more invasive surgical procedure. I have a hard time understanding how her insurance is able to deny a claim for fibroid treatment for a 20-week sized uterus."

Dr. Kaufman at OHSU wrote a lengthy letter on behalf of Triplett to Regence Blue Cross Blue Shield.

"I believe that artery embolization was indicated for treatment of Ms. Triplett's uterine fibroids and should be covered," Kaufman wrote in his summary.

Likewise, Rainford's physicians have also written letters to Regence explaining why the embolization was medically necessary.

"Because she had multiple and large uterine fibroids, surgery would have entailed multiple incisions in the uterus for multiple myomectomies," writes Dr. John Berstrom of Rainford. "If (Rainford) would choose to have a pregnancy thereafter, she would stand a very high risk of uterine rupture with disastrous results. Embolization therefore seemed to be the best procedure for her and this was ... recommended as the safest and most conservative treatment."

The question both women started asking after receiving huge bills for their embolizations was this: If their doctors were not the ones deciding if embolization was "medically necessary," who was?

Regence now says it is not up to physicians to decide if embolizations are medically necessary. Instead, in a letter sent to Rainford a few months ago, the insurance provider states that, "The fact that a professional provider may prescribe, order, recommend or approve a service or supply does not, of itself, make the service or supply medically necessary."

As Rainford learned, in that same letter from Regence, it is the insurance company's own claims administrator – not the physicians — who "determines whether the services are necessary in consultation with professional consultants, peer review committees or other appropriate sources..."

"It just makes me second-guess myself," Rainford says. "I thought I'd done everything necessary to make sure that this was going to be covered. I even paid for the most expensive plan through my work ... I was told that preauthorization was not necessary with my plan."

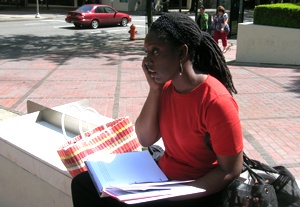

Nearly one year after receiving what their doctors said was a medically necessary procedure – one that would take care of their fibroids without sterilizing the women – Triplett and Rainford are still fighting Regence – the largest insurance provider in the Pacific Northwest that serves more than three million members and has more than $6.5 billion in annual premiums — to get the insurance coverage they expected.

"I wake up with panic attacks now," Rainford says. "This has been my number one priority. It's just so frustrating. I mean, who can afford to pay $20,000 just like that? This has ruined a significant chunk of my life."

- Home

- News

- Opinion

- Entertainment

- Classified

- About Us

MLK Breakfast

MLK Breakfast- Community

- Foundation

- Obituaries

- Donate

04-23-2024 11:28 pm • PDX and SEA Weather