If it passes, an Oregon House bill would be the first of its kind to require lawmakers to think about how a law might contribute to Oregon's disproportionate minority prison population.

The bill's sponsor, Rep. Chip Shields, D-Northeast Portland, said the bill would keep imprisoned minorities in the spotlight.

"There's no doubt minorities are disproportionately impacted by sentencing and criminal justice policies," Shields said.

Much like laws requiring the legislature to draft fiscal and environmental impact statements for potential legislation, Shields said House Bill 2933 would force lawmakers to confront how laws might disproportionately affect communities of color, but would not prevent lawmakers from passing racially biased legislation.

The push to add race transparency to sentencing laws began when Salem defense attorney Jesse Barton was making a speech to Uhuru Sa Sa, a Black inmate self-help group. He asked how many had received aggravated departures – sentences above the standard sentencing range. More than one-third of the inmate's hands – Black hands — went up. That's when Barton decided to seek a solution.

"The longer you stay in prison, the harder it is to readjust," Barton said.

It's no secret that sentencing, enforcement and other criminal justice policies have had a disparate effect on minority communities.

According to the Bureau of Justice, as of 2005, Black males have a 32 percent chance of serving time in prison at some point in their lives. White men have a six percent chance. Two years ago, 40 percent of this country's prison inmates were Black and 20 percent were Hispanic. In 2005, one in eight Black males in their late 20s was incarcerated compared to one in 59 White males in the same age group.

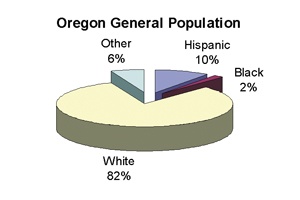

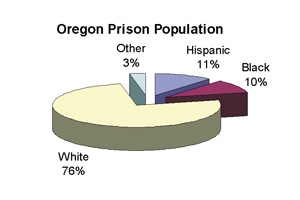

In Oregon's state prisons, 10 percent of inmates are Black, 76 percent are White and 11 percent are Hispanic.

Of the approximately 65,500 Blacks living in Oregon, more than 1,300 are living in a state prison – that's 2 percent of Black Oregonians. In contrast, only .3 percent of White Oregonians .4 percent of Hispanic Oregonians are in state prisons.

Barton believes lawmakers need to understand these numbers and be aware of these disparities when they're considering legislation.

"They've been passing criminal justice laws without thinking about racial disparities," Barton said. "They've never seen this stuff."

In some cases, Barton said people have challenged laws on racial disparity, an argument that is countered by claims that the law's disparity was mere happenstance.

Barton thinks lawmakers might not be so quick to pass laws that have the potential to make things worse for minorities if they could see the research beforehand.

"... What if the legislature knew going in they would create racial disparities?" Barton asked.

Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, thinks a lot might change if legislators were more aware of what their laws might do in the future. Mauer's organization examines where racial disparities come from and to what extent the disparity is warranted or unwarranted.

"We've seen legislation that might have an effect on racial disparity be adopted in 20 minutes but can take 20 years to break down," Mauer said.

To understand how some laws lead to disparities in prison populations, just look at legislation related to the "war on drugs."

One piece of "drug war" legislation that has negatively affected the Black community is the sentencing guidelines related to rock versus powder cocaine.

The amount of crack cocaine – a drug more often found in communities of color – that it takes to get a mandatory minimum sentence is much smaller than the amount of powder cocaine – more common with White drug users.

It takes just 3.5 grams of crack cocaine, the amount that one user might go through in the course of a few days, to receive a mandatory minimum sentence but it takes 454 grams of powder cocaine – nearly 2,300 lines of cocaine – to get the same sentence.

According to testimony from Jasmine Tyler, deputy director of the Office of National Affairs, although more than 66 percent of all crack/cocaine users are White, 80 percent of those who have been sentenced under federal crack statutes are Black and only 8 percent are White.

As written, House Bill 2933 would provide a standard for developing racial and ethnic impact statements. Changes in rules for parole would also require such statements, but most prisoners are no longer eligible for parole due to Oregon's Truth in Sentencing legislation.

The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission would conduct the impact studies. But would the commission be the most impartial authority to conduct such a study? Shields said the study could be completed by a variety of agencies that employ researchers, or it could be contracted out to a private company.

Saying that having a large segment of the minority population behind bars is "not a good situation," Mauer said he expects similar bills to pop up in other states over the next few years.

The idea is new and has no organized opposition, but Shields and Barton say the 2007 session doesn't appear to be the year for racial impact studies. The bill is currently waiting for a hearing in the House Judiciary Committee. The bill will die if it is not pushed out of committee — or moved to another committee — by the end of April.

Barton said a new idea sometimes needs time to gather momentum.

"Conceptually it's a good idea," he said. "You have to start somewhere. Every bill has its day."