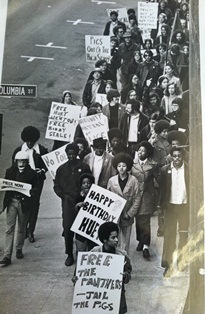

Photo courtesy of the Portland Archives |

When people think of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, they might think of black berets, leather jackets, guns and COINTELPRO. What's often lost is the story behind their origins, their emphasis on reading and understanding the law, and discussion of their survival programs. What also tends to get lost is the story of chapters outside of the national headquarters.

Both Portland and Seattle had thriving chapters. Kent Ford and Aaron Dixon of the Portland and Seattle Panthers, respectively, explain some of the lesser known points about the party in a Skanner News Black History Month special feature.

Origins

"The climate was the same as it was everywhere else in the U.S.," says Ford. "Bigotry.

Kent Ford |

Racism. Poverty. Unemployment. The conditions were right for organizing."

Ford, a Portland transplant from Richmond, California by way of Louisiana, was himself, a victim of police brutality. Although he says he had a good living and didn't have to get into social justice work, he saw that the community was in need. Ford was also influenced by reading the works of Malcolm X and Mao Zedong, as well as his following of anti-colonial struggles taking place in third world countries during the 60s. The combination of rampant police brutality and his continued search for enlightenment led to him starting the Portland chapter of the Panthers in 1969.

Dixon was heavily influenced by the oral tradition in the Black community, and in his family in particular. He lived with his great grandmother who was born in 1867 and told stories of her mother, who was a slave. The oral tradition, he says, was essential in educating and preparing Black youth to carry on the struggles of those that came before them. It was based on the concept that it takes a village to raise a child.

Dixon says his family would always watch the news to keep abreast of the civil rights movement in the South. Once he got to University of Washington, he helped found the institution's first Black Student Union and quickly found himself in jail for organizing a sit-in in 1968. While in jail, he got the news of Dr. Martin Luther King's assassination. He says it was particularly jarring because he and his peers had marched with Dr. King in Seattle for housing justice.

"I remember that night, going back to my bunk and thinking about Martin being killed," he says. "I remember saying to myself, 'For me, the picket sign was going to be replaced by the gun.' I didn't realize that all across the country, other young people were thinking the same thing. We had grown up watching the civil rights movement. We were going to start something in its place. For us, that was the Black Panthers."

Aaron Dixon |

Literature and Law

The Panthers were founded in 1966 by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. At the time, Newton was a law student and Seale was an architectural, structural engineer. Dixon says they were both well read.

When he first approached Seale about starting a chapter in Seattle, Dixon was given a list of 25 books and told all members were required to read two hours a day. They were also required to attend political education classes twice a week.

In addition to the book list, Dixon says he was told he needed to have two weapons and two thousand rounds of ammunition.

Newton was a proponent of the Constitution and emphasized educating party members on their 2nd Amendment Rights. This included teaching them how to carry their guns, clean them and what the laws were for using their weapons.

What resulted was the Panthers' first program, which was police patrol. Members would get their tape recorders, shotguns and law books and follow the police when they stopped Black people in their community. The members would stand the required distance from the scene, inform the police that they had the right to observe and inform the person stopped that he/she only had to give the officers his/her name, address and social security number.

Ford and Dixon imitated this program to respond to the police brutality that was rampant in their own communities.

"The police were so brutal in those days," says Ford. "They had to have somebody to stand up to them. Not just protesting but with the same thing they had. No tactic was too low for them to pull."

He says that renegade officers with particularly troubling racist mindsets were assigned to Black areas in Portland so they would come down on the Black community harder.

In addition to observing stops, Portland Panthers would go downtown to bail people out if they were arrested. They also provided community members with a legal fact sheet and a number to call if they found themselves being victimized by the police.

Survival Programs

Although the guns and confrontations with police dominated the media coverage, infamous FBI director J. Edgar Hoover actually deemed the Panthers' Free Breakfast Program as the biggest threat to national security at the time.

Dixon says that survival programs like this were part of the party's evolution.

"Because we read a lot we understood that nothing stands outside of change," he says. "We were not wedded to one thing we were going to do. We understood that we were always having to change what we did from one year before."

By 1969, Dixon says members stopped wearing the traditional uniforms of black berets and leather jackets because they were alienating themselves from the rest of the community. Also, gun laws targeting the Panthers were passed in Oakland and Seattle at the time so they had to stop carrying their weapons.

One of the first needs the Panthers addressed was children going to school hungry. A number of social programs were cut in response to the Vietnam War so they started the first free community breakfast programs in the country (These programs have since been adopted by the federal government and many still exist today). At the height of these programs, Panther in places like Chicago and L.A. were feeding thousands of children, says Dixon.

His chapter also founded a free medical clinic.

These programs were integral in Portland too, says Ford.

He says the Portland Panthers' free breakfast program was feeding anywhere between 75-125 kids a day.

They also created the Fred Hampton People's Health Clinic and the Malcolm X Dental Clinic, which were located on North Williams Avenue.

"We had pimps, prostitutes and everything and that's where we decided to put our clinic," says Ford. "That's where we decided it was needed."

The health clinic was open five days a week from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. It had 30 doctors who were all specialists and 15 nurses. After the health clinic emerged, dentists came forward and offered their services. All of the workers at the clinics were volunteers.

Dixon adds that there were a number of other services available, depending on which chapter one was closest to . For example, he says there was a free ambulance program in Harlem, as well as an evidence program in North Carolina.

"Wherever there was a need in the community, we developed programs around them," says Dixon. "We found volunteers in the community to facilitate programs. We really empowered a lot of single mothers and welfare mothers who took over our Breakfast program."

Coalitions Building

The initial purpose for Newton and Seale forming the Panthers was to continue the work of Malcolm X, who had been developing an internationalist approach to the Black struggle, which united American Blacks with oppressed people of all colors throughout the world.

Dixon says this is what made the Panthers particularly threatening.

"We understood the importance of broad coalition building," he says. "We built broad coalitions with a lot of different people. The Brown Berets. The Red Guard. AIM (The American Indian Movement). We also had broad coalitions with the Peace and Freedom Party, a white organization that ran Black Panthers as political candidates. We understood that it wasn't just about Black people. This was an international struggle against oppression and capitalism and imperialism. We understood that there were poor whites, poor Latinos, poor Asian people, poor Native Americans.

"This is what made the Black Panther Party so dangerous. We had a large base."

Another aspect of the Panthers' internationalist focus was the national, weekly Black Panther newspaper. Dixon says members of his chapter were each required to sell 100 a day. At its height, he says the paper was the most popular alternative publication in the world, with a circulation of 350,000.

Ford says the Portland chapter was selling 5,000 papers a month.

He says the FBI went as far as to fund other news outlets to try and counter the paper's influence.

"Nobody paid us," says Ford. "We weren't on anybody's payroll. We made do with what we had. We still put on a better performance than the government who put up the money to pay the people to do it."

Kent Ford's son Patrice Lumumba Ford is currently serving 18 years in federal prison on what his father says are politicized charges. Lumumba Ford was part of what local media dubbed "The Portland Seven." According to his father, Lumumba and five other men traveled to China in Oct. 2001 to request visas so they could travel to Pakistan. He says they were alarmed by the thousands of Afghanis fleeing to refugee camps in Pakistan following the U.S. led invasion of Afghanistan. The visas were denied and a year went by before Lumumba and his companions were swept up in synchronized arrests of alleged terrorism suspects in Portland, Detroit, Seattle and Lackawanna, New York. Kent Ford believes his son received such a harsh sentence because he refused to cooperate with the Justice Department and help them prosecute other Muslims. In addition to his unwillingness to be an informant, Kent Ford also believes his son was targeted because of his father's reputation and history of political resistance. During a Skanner News examination of Portland Police surveillance files from the 1960s and 70s, Lumumba Ford's name does appear in connection with his father, even though he was a small child at the time. Kent Ford encourages people interested in his son's case to write to Lumumba, as well as write to U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder. Lumumba has already served ten years. To write Patrice Lumumba Ford: Patrice Lumumba Ford, 96639-011 USP Pollock P.O. Box 2099 Pollock, LA 71467 |