Graduates of the program celebrated with mentors in July. The entire group graduated in six months, instead of a year, because they worked so hard to achieve their goals Graduates of the program celebrated with mentors in July. The entire group graduated in six months, instead of a year, because they worked so hard to achieve their goals |

DeAndre Frison is completely open about his troubled teen years. He was just 13 when he was sentenced to juvenile detention. And just before his 18th birthday he went to prison for shooting at a car full of rival gang members. Legally an adult when he started his 60-month mandatory sentence, he says, inside he was just a boy.

"It was definitely scary, the uncertainty of what would happen," he says. "I'm not really a man, though I am in the eyes of the state."

Released in 2009, Frison was one of a group considered at high-risk for reoffending: young people under 25 who have a history of crime and incarceration as a youth.

DeAndre Frison: Read his full story in Part Two DeAndre Frison: Read his full story in Part Two |

But in 2010, he graduated from a program designed to reduce that risk, the CPR re-entry program, run by Volunteers of America.

Today, Frison holds down two jobs. From 6.m. to 2:30 p.m. he is a tradesman with a local Steel company. From there he goes back to CPR -- this time as a mentor, helping other young men leaving prison.

"He's a really solid young man and I am so proud of him," says Kathy Sevos, the CPR program director. "These young men are really beating the odds. It's tough out there."

More than 75 Percent Do Not Reoffend

CPR stands for Community Partnerships Reinvestment, but it's tempting to think of it more in the medical sense, as CPR for young offenders. Because, while it doesn't actually kickstart hearts that have stopped beating, this program does seem to stop young men from throwing their lives away.

Family, friends and supporters came to VOA's Velma Joy Burnie Center in July to celebrate with the program graduates Family, friends and supporters came to VOA's Velma Joy Burnie Center in July to celebrate with the program graduates |

A five-year follow up study by Portland State University in 2010, found that more than 75 percent of those who take part in the program stay free of felony convictions.

For all crime, the study found, the rate of reoffending for CPR alumni is 32 percent compared to 50 percent for all high-risk young offenders in Multnomah County. And when you consider that the 50 percent figure includes the CPR group, the numbers look even better.

"We actually brought that number down; we dropped the average," Sevos says. "Because our group is a subset of the larger group."

CPR starts behind the walls of three prisons: Oregon State Penitentiary, Oregon State Correctional Institution and Columbia River Correctional Institution. High-risk young offenders are offered a chance to join the program, but participation is completely voluntary. CPR works with 58 men at a time, taking in about 6 new participants a month.

Once in the program, the men take part in cognitive behavioral therapy sessions, designed to change negative, or criminal, thought and behavior patterns. For six months before they are released, they spend at least six hours a week working with parole officers, counselors and mentors to set goals for themselves and plan for release.

Then, on the outside, they continue in the program for a year, attending groups, meeting with case managers and following through with their plans.

CPR graduate Benjamin Miller with his mom Sonja Miller. After struggling with heroin addiction, Ben has been clean and sober for 15 months and works full time. "This is so huge," his PO said at the graduation. "As parole officers, we don't often see this kind of success." CPR graduate Benjamin Miller with his mom Sonja Miller. After struggling with heroin addiction, Ben has been clean and sober for 15 months and works full time. "This is so huge," his PO said at the graduation. "As parole officers, we don't often see this kind of success."Miller said he would not have made it, if he'd been living on the streets, but through CPR had been able to find housing. |

The Men Struggle to Find Jobs

Leaving prison behind is not easy. Young men with felony convictions struggle to find jobs.

Marina Poltorak, transition coordinator for the CPR program, says financial insecurity and unemployment are the reality for most of the men.

"Surviving the process of not getting a job is the biggest challenge, with the economy the way it is and their history of incarceration," she says. "A lot of the young men I meet have never had an above board job, and they almost never have high school diplomas.

"Those who do get a job, they get it because their families help them."

About 40 percent of CPR participants are fathers, Sevos says. They want to support their families, but the reality of the jobs market makes that impossible.

"Sometimes the women are the ones who help them survive," she says. "That is one of the things that helps stabilize them: if they can get jobs.

"Most of the men are very under-employed. They find work but it's very low income. We call those survival jobs."

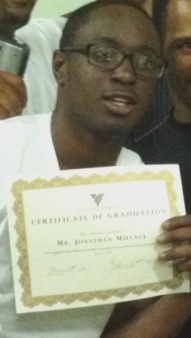

"Integrity is what comes to mind," said P.O. Travis Gamble of program graduate, Jonathan Millage (above). "This is somebody if I tell him to be there at 10:30, he's there at 10:15. I can believe anything he tells me, and that goes a long way." "Integrity is what comes to mind," said P.O. Travis Gamble of program graduate, Jonathan Millage (above). "This is somebody if I tell him to be there at 10:30, he's there at 10:15. I can believe anything he tells me, and that goes a long way." |

Study: CPR Saved Oregon $1.35 million

"I'm very thankful I got to work with DeAngelo," said Carolyn Ferreira, an intern from the Pacific University Psychology Doctorate program. "I asked him what tools he was going to use to cope, and he said 'What tools don't I have?' That's his mentality." Read DeAngelo's story in Part Two |

The average cost of the CPR program is about $6,100 per person. That's peanuts compared to the cost of incarcerating an offender. The Portland State study said that for each class of 58 men, CPR potentially saves society $1.35 million.

CPR is funded by Oregon's Department of Corrections, Multnomah County's Department of Community Justice and some smaller private grants. For the next two years, its mentor program is guaranteed funding through the federal, "Second Chance" program.

Volunteers of America also partners with SE Works, Metropolitan Family Services and the Constructing Hope pre-apprenticeship trades program.

Just like other teens and 20-somethings, these young men want to make their own decisions. They want to have nice clothes, stylish shoes and cell phones so they can text with friends.

"Can you imagine not having a cell phone at that age," Sevos says. "They can't buy that nice watch, and they have no money for clothes. It's the bling and the flash, and having stuff. They don't have parents who will put that on their credit cards."

As felons, these young men have to fight their way up from the bottom of our society. At the July graduation, counselors, parole officers and mentors spoke about how hard they work to do so. One man took two part-time jobs. Some men have to distance from family and old friends just to stay out of trouble. All of them have to consistently attend meetings, follow their recovery programs and meet their goals.

Sometimes they slip up.

"Developmentally, we think of them more as adolescents," Sevos says. "Their development has been stunted and they don't know anything except what they have experienced. The fact of the matter is they do have trial and error, and they are doing that in a culture of drugs and guns and crime, where their friends are all still in it.

"OK, it's your 21st birthday and you got drunk with your old buddies and got a DUII. Or maybe, they just don't go to see their parole officer. We work with them to mitigate those mistakes. Because whether it's small or large, if you're already a convicted felon then you are far more likely to go back to prison.

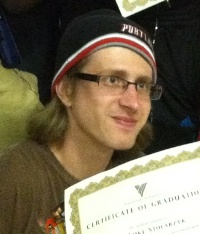

Luke "Skywalker" Stolarzyk Luke "Skywalker" Stolarzykhas a 4.0 GPA at community college and works an alcohol recovery program. At the CPR graduation, program coordinator Marina Poltorak told Luke: "You didn't lie. You did exactly what you said you were going to do. I'm extremely proud of you." |

"They are labeled and that has long-term effects," Sevos says. "They can change their attitudes. They can change the peers they hang out with – their anti-social friends and acquaintances. But if you've been incarcerated as a young person, you can never really get away from that. In terms of risk you can never erase the fact that someone was locked up at age 15."

Mentors who have survived the same challenges of incarceration and rehabilitation are a key part of the program. Kate Desmond, supervisor of gang intervention programs with Multnomah County's Community Justice says mentoring and peer support help make the CPR program successful.

"What I like so much is that this program allows participants to have an active role in their recovery and in making good choices for themselves," she says. "They hold each other accountable. It's easier for them to be held accountable by the group. 'Hey you said you were going to do A, B. and C, when you were inside.' So they can be very supportive of each other in making the right decisions."

Part Two: A Mentor and a Graduate seize their second chance