Lisa Loving photo |

By Lisa Loving Of The Skanner News

Tamberlee Tarver's son Camron has been suspended from his North Portland school nine times since last October.

He's run away from teachers, tried to run away from school, spit on a teacher and thrown papers on the floor.

Camron has a short list of disabilities impacting his coordination and his ability to focus – and now is being treated for an anxiety disorder.

A kindergartner, Camron is five years old.

"I'm currently looking for a therapist to undo some of the damage that's been done so far – because my son's turned into a whole different person," Tarver says.

Who knew such little kids could be kicked out of school? But a 2005 study by Yale University found that in Oregon, preschoolers are expelled at twice the rate of school-aged kids, and that black toddlers are expelled at about twice the rate of white tots – even higher than the national average.

Not only are the littlest African American students banished from classes at higher rates than their teenaged counterparts, but nationwide, Black students are punished with classroom dismissals at a far higher rate than any other group throughout the K-12 system – especially if they're in special education programs.

Yet, many researchers say, there is no evidence that Black kids act out more than any others.

Despite the fact that the dynamic has been known and recognized for generations, many educational policymakers have been slow to move on the evidence that hundreds of millions of dollars could be saved nationwide by state and local governments with one simple policy: use suspensions and expulsions as -- genuinely -- a final resort.

Can reducing the use of kiddie racial profiling to discipline youth by kicking them out of class be the key to reducing the achievement gap – and the incarceration rate?

New Obama Policy

Last July, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder and Education Secretary Arne Duncan together rolled out the Supportive School Discipline initiative, dedicated to addressing "the 'school-to-prison pipeline' and the disciplinary policies and practices that can push students out of school and into the justice system," the Justice Department said.

Last July, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder and Education Secretary Arne Duncan together rolled out the Supportive School Discipline initiative, dedicated to addressing "the 'school-to-prison pipeline' and the disciplinary policies and practices that can push students out of school and into the justice system," the Justice Department said.

"The initiative aims to support good discipline practices to foster safe and productive learning environments in every classroom."

The policy came in response to a massive University of Texas study tracking nearly one million seventh graders for three years. The data showed the vast majority had at least one suspension -- 84 percent for boys, 70 for girls. Black students were 31 percent more likely to receive a "school discretionary action" than white or Hispanic students.

"Ensuring that our educational system is a doorway to opportunity – and not a point of entry to our criminal justice system – is a critical, and achievable, goal," Holder, at left, said in a statement last summer. "By bringing together government, law enforcement, academic, and community leaders, I'm confident that we can make certain that school discipline policies are enforced fairly and do not become obstacles to future growth, progress, and achievement."

'Literally Decades'

Oregon Rep. Lew Frederick, D-Portland, spent many years as the public information officer for the Portland Public Schools; before that he was a television news reporter. He says he's not surprised by the idea that kicking students out of the classroom holds them back in the long run.

Oregon Rep. Lew Frederick, D-Portland, spent many years as the public information officer for the Portland Public Schools; before that he was a television news reporter. He says he's not surprised by the idea that kicking students out of the classroom holds them back in the long run.

"We have seen this kind of indication for literally decades," he says. "We know what works, we just have, for various reasons, political philosophical and otherwise, decided that we're not going to do what works."

Frederick says that back in the 70s, part of the Portland schools desegregation plan was "the concern about the kind of impact that suspensions and expulsions have on minority kids, black kids in particular, and that in fact was feeding the pipeline for kids going into the prison system.

"By showing an increasing number of black kids that are being suspended and expelled, you were also finding a disproportionate number of kids in juvenile detention, because they were being expelled and sent home without supervision, in part because they didn't have the family structure to provide supervision – there was this 'Leave It to Beaver' belief that mom was going to be there and hand out discipline there when it clearly was not going to be the case."

Tarver expands on that point.

"My son came from Albina Head Start where he did two years successfully. But the dynamics of the program are completely different, where there's a higher teacher to student ratio, there's more support, there's more services that come into the classroom and work with the children," she said.

"So I can see the difference but I think some of it is a matter of power too. How much do they tolerate, and how much do they work to keep the child in the school? Because Albina Head Start, their philosophy is to work with the family as a whole, if there's a problem with the child they embrace the family to say, okay we have this service to see what's wrong with your kid, and they try to work with the family to help the kid, not just to send the kid home and tell the family to figure it out."

The Data

In Washington State, education officials have yet to agree on any statistical data on the "push out" issue; in Oregon, there's plenty.

"More than a third of Oregon young people who have been incarcerated are convicted of felonies within three years of their release," reported the Annie E. Casey Foundation last year in their study, "No Place for Kids: The Case for Reducing Juvenile Incarceration."

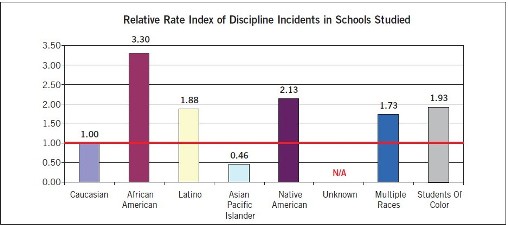

From 'Exclusionary Discipline in Multnomah County Schools: How Suspensions and Expulsions Impact Students of Color,' courtesy the Multnomah County Department of Community Justice From 'Exclusionary Discipline in Multnomah County Schools: How Suspensions and Expulsions Impact Students of Color,' courtesy the Multnomah County Department of Community Justice |

Meanwhile, a new study by Multnomah County's Commission on Children, Families & Community shows nearly 40 percent of African American school kids throughout Multnomah County experience suspension or expulsion, almost 3.5 times the rate of white students.

Oregon State Department of Education spokeswoman Crystal Green listed off local school districts that have landed on a list for disproportionate discipline of special education students.

-- In 2011: Portland Public Schools and Woodburn School District;

-- In 2010: Woodburn, Beaverton and Tigard/Tualatin;

-- In 2009: Eugene, Portland, and Tigard/Tualatin.

"There's a highly complicated formula that looks for, are too many minority special ed kids being identified for special ed, and are the minority special education kids being disproportionally disciplined," Green said. "I've definitely heard principals from schools doing this work and being successful in this work saying, you don't want to believe it's perception, but everyone comes into these things with their own judgments. So we just want to make sure that peoples' awareness is really there on this issue."

Civil Rights

In Seattle, the Post-Intelligencer newspaper has reported on the disparities for 10 years; school officials say they've set up a committee to look into the issue and they're just now beginning to collect data district-wide and they'll make it available in 2013.

In the Highline School District, in Burien, Wa., black students are 11 percent of the classroom population. Highline Middle Schools are Cascade, Chinook, Pacific, and Sylvester. Table courtesy Steve Trubow, Olympic Behavior Labs |

That's not soon enough for one researcher, who has already obtained the raw data and crunched the numbers. Steve Trubow of the Olympic Research Laboratory -- a crime-prevention research organization in Port Angeles, Wa. -- has filed civil rights complaints against 19 school districts across the state in the past few months.

His findings:

• In Highline Public Schools, where white special ed students outnumber black special ed students 2 to 1, the black students comprise 57 percent of the suspension rate;

• The disproportionality rate in Seattle, Issaquah and Battle Ground shows black students suspended or expelled at four times the rate of white students;

• Black students are expelled or suspended at five times the rate of white students in Bremerton and Shelton

• InBellingham schools, black students with IEPs are suspended or expelled at seven times the rate of white students with IEPs;

• In Pasco, the African American students with IEPs are suspended or expelled at 28 times the rate of their white counterparts.

(Individualized Education Plans are required for special education students by the federal Individualized Education Program; they are particularly intended to make clear to teachers and teaching assistants what an individual student's disability is and how to accommodate the child to improve learning outcomes.)

Trubow has researched statistical data on school push-out in cities all over the United States. Last year the federal government initiated a Civil Rights investigation of Santa Barbara schools after he filed an official complaint with the Department of Education.

A study in which he is a co-author, "State of Emergency: Addressing Gang Violence and the Drop Out Problem," is part of the Congressional record. He testified before a Congressional subcommittee on the issue in Washington, D.C. in 2009; that, too, is part of the Congressional record.

"What we've done a lot of research in is the risk factors -- either individual risk factors, family city or school -- that lead kids into gangs and drugs and violence and other dangerous behaviors, even teen suicide," Trubow says.

"It costs a lot of money to incarcerate people; in King County to lock up an adult is $48,000, but to lock up a juvenile it's over $100,000 a year.

"So instead of suspending children and expelling them from school and putting them into the school to prison pipeline, it would be a whole lot less money and save a lot of children from going into the courts, from being arrested, from being prosecuted – that is in Washington State right now we're spending eight times the amount of money locking people up as we are on public education -- it's eight times the amount," he said.

Harsher Punishments

The new Multnomah County report, "Exclusionary Discipline in Multnomah County Schools: How Suspensions and Expulsions Impact Students of Color," links early-childhood school exclusions to the drop-out rate, youth violence and incarceration.

The document is truly a milestone; its authors describe it as "the first time our community has been able to compare discipline data, disaggregated by race, across all districts using shared definitions and assumptions." It was commissioned by the Commission on Children, Families & Community and the SUN Service System.

"Nationally, Caucasian students are referred to the office significantly more frequently for offenses that can be objectively documented (e.g.smoking, vandalism, leaving without permission and obscene language)," it says.

"African-American students, in contrast, are referred more often for disrespect, excessive noise, threat and loitering — behaviors that would seem to require more subjective judgment on the part of the referring agent. And, on a national level, students of color facing discipline for the first time are typically given harsher, out-of-school suspension, rather than in-school suspensions, more often than white students," according to the report.

Tarver says this experience at her son's school. The boy was well-behaved during his mom's interview with the Skanner News despite the fact that the game he brought to play with didn't work.

"I feel that as an educator, if you're dealing with my child, you should have some type of understanding of what he is dealing with and how you can accommodate that," Tarver says. "Not just that you see a kid who doesn't want to do the assignment, well he throws it on the floor. To them that is being defiant; to him it means I can't do this writing assignment, my hand hurts because I've been writing this long sentence with a lot of letters and my skills aren't up to par. That's what that means to him.

"But to the teacher, he just doesn't want to do the work, he's not listening. That's a 'go home' offense. That's open defiance, that's insubordination. There are all kinds of labels and offenses that criminalize our children. They're all about do what I say and do it now or get out.

"Those who can't comply immediately or conform with minimal assistance will not be tolerated in a traditional Portland Public Schools classroom – like my son, Camron."

'Open Defiance'

Daniel Losen is the director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project. His most recent research in October of 2011 was called, "Kicked Out and Then a Dropout."

Daniel Losen is the director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project. His most recent research in October of 2011 was called, "Kicked Out and Then a Dropout."

The study was a compilation of research showing the extent of discipline for "mostly mundane kinds of offenses like truancy, dress code violations, insubordination, foul language, that sort of thing -- minor nonviolent offenses," he told The Skanner News.

Over and over again Losen's research reveals elementary, middle and high schools suspending kids at very high rates, but it also shows that among those high rates the highest are often for African American kids, other students of color, kids with disabilities, and especially minority kids with disabilities.

Losen's most recent study also looks at what works in terms of discipline of students.

"It shows that there are alternatives to kicking kids out of school and onto the streets that work much better, and that in fact when you suspend large numbers it's a predictor of kids dropping out," he said.

"In other words it's contributing to our low graduation rates, this advent of zero tolerance," Losen says. "And so what it really suggests is that this kind of suspension is not educationally sound, it's not good for any kids -- but this unsound practice is burdening kids of color a lot more than other kids.

"And it can be replaced, there are more effective ways to do it and therefore really it suggests as a matter of policy and practice that things have got to change."

Parents Networking

Tammy Tarver is already working on change. She recently testified before Gov. John Kitzhaber's Oregon Education Investment Board; the following week the board announced they're holding a community forum for parents in North Portland.

"We've got a group of parents – there are some whose kids are on an IEP (Individualized Education Plan), but it's an old IEP and it has not been updated. There are parents who their kids are also on an IEP and they're getting suspended on a regular basis too, or referrals. Getting some type of disciplinary action.

OTHER ARTICLES: |

"For me I think it's a low tolerance of kids that are different. Kids with different abilities. Those kids who can't come and be a clone to the other ones, who can't be still and shut up and just listen. Okay now we're going to let you jump around for a bit, take five minutes and get up and jump around and then come back and sit down.

"I'm telling them – my son has sensory processing disorder," Tarver told The Skanner News. "The way he takes in the information, he may misinterpret what's going on, he may not understand it, there may be too much information coming towards him – it could be a number of different things.

"But they're the professionals with the letters after their names, you know?"

Next: Part 2: Solutions – and Failures